In our new series State of Synch we reach out to industry leaders from different fields to get their opinion on where we stand. How do ongoing technical developments, market shifts, customer behaviour and the global economy impact our playing field – and what do we intend to do about it? Kicking this series off is Fabian Schütze, whos excellent bi-weekly newsletter “Low Budget High Spirit” is not only higly recommended, but has become a warmly received standard-read among the wider independent music sector. You can subscribe for free here.

State of Synch with Fabian Schütze

It’s been a while since I’ve written about sync here. But recently I’ve stumbled across some interesting articles on the subject. I’m currently working on syncs in some of my own projects and have definitely had some “ yikes” moments over the past year. If you take a closer look at the developments in this industry segment in recent years, it becomes clear just how much turmoil is being caused by the meta trends.

The Netflix gold rush

In the early years the sync industry was generally relaxed about the disruption of music digitization (Napster, iTunes, Spotify). Along the lines of: whatever, we have nothing to do with it. We don’t care how consumers listen to music as long as advertisers continue to pay for it. And as long as people go to the movies and watch the films in which our music is placed.

Things around the internet only got really interesting late on: with the launch of Netflix and the entire video-on-demand economy that it created. Suddenly, there were several global corporations in fierce competition, which – in addition to cinema – produced a huge number of new films and, above all, series and therefore needed a lot of music. And thanks to the internet and apps like Shazam or social media and GEMA (German royalty collecting society), these syncs are not only worth the flat fee that Netflix pays. They are also able to build real careers, drive Spotify streams and generate plenty of additional royalties. So the gold rush began. There are many reasons why, just a few years later, the average licenses paid have already fallen significantly.

Much more image content is being produced, but there will always be considerably more music out there. The relation of supply and demand is just not right. There is always someone who has an equally suitable song but offers it for a cheaper price. In addition, Netflix has naturally been quick to recognize how much value these placements have over and above the fee they pay. In addition, tech companies now have to become profitable. After years in which it was all about increasing market share, subscriber numbers and sales, they are now working hard to optimize another KPI: profit. And that means laying people off, increasing subscription prices and reducing production costs.

The atomization of marketing and content

Before the internet and social media, things were pretty simple. There were a few thousand companies in the world that bought music for sync. Namely companies that produced cinema or TV films or could afford to run TV commercials or occasionally radio spots. It’s different now. Today, everyone can create content and use it to market their products. Today, there are licenses for the smallest social media campaign, YouTube videos, micro-syncs for apps, gaming, use in media libraries and much more. The big problem is that these are all small amounts – but the process itself is just as much work, regardless of the amount on the invoice. For both licensors and licensees. In a highly recommended article on musicbusinessworldwide.com on the subject, Tom Stingemore (former high-ranking sync manager at Hipgnosis and Universal) summarizes it as follows:

«Record labels & music publishing licensing executives are now drowning in a sea of smaller, lower-value sync requests (…) The amount of time being spent on this deluge of smaller sync deals is highly inefficient, but perhaps even more troubling is the fact that brands / agencies / productions that want to use our copyrights are now simply moving away from using commercial music.»

‘Cause what are they using instead?

Better use AI

This is not a prediction, but a reality already: the entire area of “functional background music” with a low level of creativity (formerly “elevator music”) is flooded by AI, then completely replaced. This will primarily affect the micro-syncs described above. For ad campaigns on TikTok by influencers and consumer brands, nobody will use real music anymore, but will do a deal with the TikTok library consisting of generic music and that’s that.

But everyone else shouldn’t feel too safe either: a big trend in sync in recent years has been cover versions of hits. The background to this is that although the copyright side has to be negotiated with the big artist / the big publisher, the master right is much cheaper because you only have to pay for the cover version of the small artist. Already today a prompt like the one below will produce an acceptable result.

Generate an acoustic cover with a modern twist of the song «Cherry Cherry Lady» by Modern Talking. Female singer, 85 bpm. Please send a mastered WAV file.

And of course, every music supervisor providing series on Netflix, Amazon, Apple TV, Disney+ and advertising campaigns is already taking very close looks at which slots can be filled with sufficiently acceptable AI music at a reasonable price.

The mechanisms of the 20th century vs. the reality of today

Everything we know about rights today comes from the 20th century or before. These mechanisms have already been shaken badly by the internet, but it is artificial intelligence that is the real nemesis. I am very pleased that the EU was unexpectedly quick to take an important first major step with the Digital Services Act / Digital Market Act. But the challenges are global, as are the players, and tend to be located outside the EU.

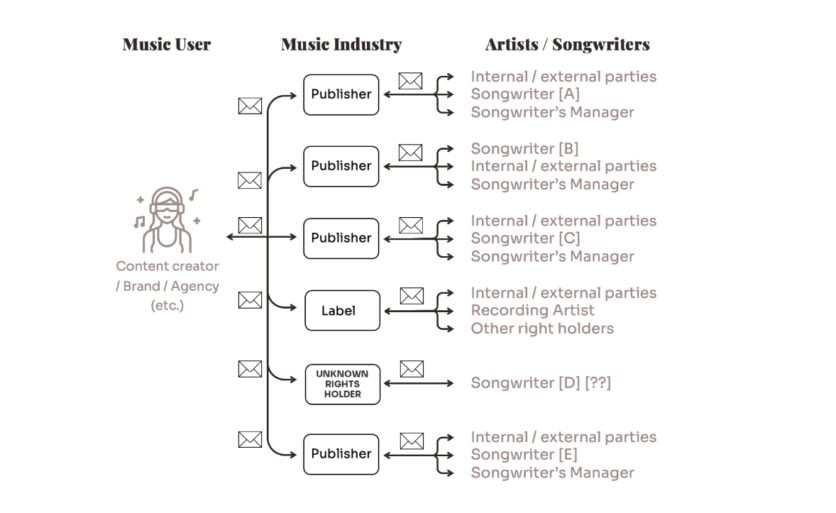

Equally problematic: while the synced music is fully digitized, everything happening in the background is still completely 20th century, i.e. paperwork. As described above, this becomes a problem when the working reality no longer consists of a few large licenses, but of many small ones. And then the communication organization chart can look something like this for the 300 euro sync fee per song.

Fun fact: the little letter symbols in the image only partly represent e-mails. They are often actual letters on paper. Of course, some people are already working on this topic, especially blockchain. But we mustn’t be under any illusions about how quickly or slowly things will fundamentally change in such an established system.

The image was taken from the article at musicbusinesswordwide.com linked above, which gave me the impulse to think about sync in detail once again. Reading recommendation:

In the article, Tom Stingemore beautifully summarizes the necessary answers and options for action. I agree on all of them, but am only listing the central one:

The music industry must join forces to protect the artists and keep itself capable of acting.